By Molly A. Seltzer

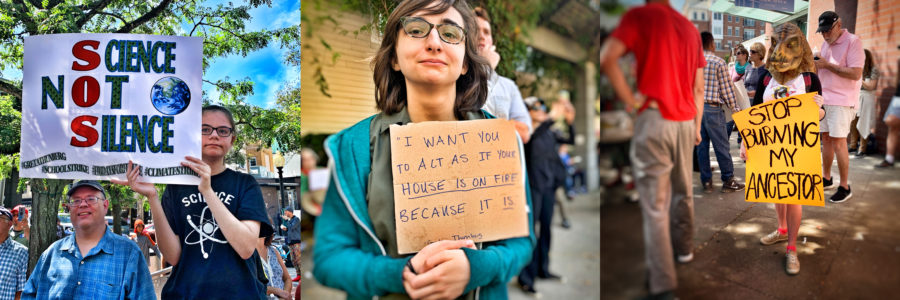

Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg has rocked the global stage as an advocate for climate action since the sixteen-year-old began skipping school to strike outside of the Swedish Parliament last year. In December 2018, she demanded a secure environmental future from international leaders at the United Nations (UN) COP24 Climate Change Conference. Her efforts galvanized millions to participate in a “Global Climate Strike,” ahead of the UN’s Climate Action Summit last month. Thunberg made a statement by traveling to New York for the meeting in a racing boat equipped with solar panels and hydro-powered generators, a zero-carbon trip, instead of by plane.

In this Q&A, behavioral psychologist Elke Weber speaks about climate messengers and the importance of showcasing personal efforts to reduce carbon footprints in cultivating support for climate policies. Weber is a Gerhard R. Andlinger Professor in Energy and the Environment, professor of psychology and public affairs, and associate director for education at the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment.

What does your research show about decision-making and cultivating buy-in? Do public figures and movements, such as Greta and the Sunrise Movement, impact decisions in the UN?

In my research I have been looking at the conditions under which a combination of grassroots movements and top-down decisions by companies or local governments might result in tipping points in our individual and collective responses to climate change. With colleagues in ecology and the complex dynamic systems modeling community, we have found that larger institutions, like the UN, play a moral coordinating role, similar to organizations at national, subnational, and corporate levels. But there is no question that mass movements by sympathetic agents, for example our sincere and scared children, focus our collective attention. The question is whether they can hold that attention when vested interests and other competing goals and objectives intervene.

Is there research that shows public figures receive more support when they showcase efforts to reduce their personal carbon footprints?

Public figures cannot expect the public to sacrifice convenience or comfort if they, themselves, do not “walk the walk.” Our prior work indicated that communicators’ carbon footprints massively affect their credibility and the likelihood that their audience will conserve energy. Our new research showed that the carbon footprints of those communicating the science not only affects their credibility, but also affects audience support for the public policies for which the communicators advocated. In a survey of 300 participants, the study found that regardless of gender, political orientation, and age of the participants, policy recommendations are better-supported when participants believe the messenger, in this case a climate researcher who conserves energy at home. The research, led by Shahzeen Attari, former postdoctoral researcher in Columbia University’s Center for Research on Environmental Decisions and now associate professor at the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, Bloomington, found it is really important that scientists, or other messengers, who communicate with the public model those behaviors that reduce carbon emissions to drive their point home.

Have you found any success stories in terms of public figures inspiring individuals?

We know that it is helpful when trusted and visible figures take action. In the United States, these figures happen to be Fortune 500 companies. My Behavioral Science for Policy Lab (BSPL) at the Andlinger Center has started a project to explore the question of whether corporate sustainability efforts and programs are impactful and in what ways. One study, headed by Sara Constantino, postdoctoral research associate in the Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment (C-PREE) and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, is forthcoming for publication, and finds that when consumers learn that companies, like Apple, Adidas, and McDonalds, are taking steps to reduce their impact on our global climate, consumers conclude that global climate is indeed an important issue, and these perceptions about climate-related norms in turn lead to greater financial contributions towards solving it.

Is there anything else we should know about how to talk about the climate challenge and framing solutions for it?

It is interesting that you chose to ask me questions about the climate “challenge,” which is halfway between climate “change” and climate “crisis” in the implied urgency for action. Most people understand that there is a looming problem. I think some cases of denial are a somewhat understandable deflection from confronting an extremely challenging global problem. Generally speaking, my sense is that the public today is more interested in learning about effective and feasible solutions than ever more details about the challenge or crisis itself. Appealing to our collective or individual ability to make progress towards solving this threat resonates and gives people hope. We, at the Andlinger Center, strive to produce research that advances solutions, and understanding the behavioral dimension of how people respond to policy options and climate research is a key piece of that.

Interested in this work? For more, follow Elke Weber and the Andlinger Center on Twitter or sign up for the Andlinger Center’s monthly newsletter.