Conference spotlights the obvious benefits and hidden challenges of a circular economy

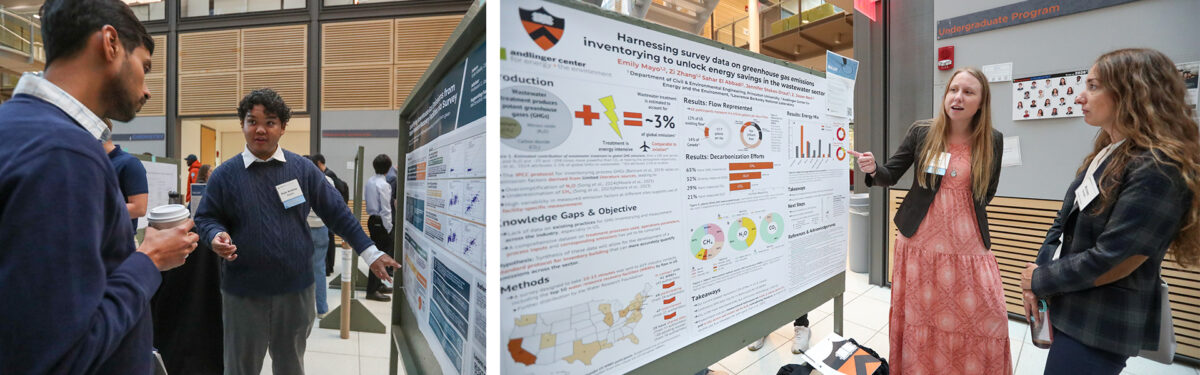

The opportunities and complexities facing a circular economy were at the heart of the 2025 Annual Meeting of the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment on Oct. 30, 2025. The day-long conference, “Strategies for Circularity: Prospects and Challenges,” brought together top experts from academia, industry, and non-profit sectors to discuss building greater circularity into our consumer systems.

Circularity refers to the concept of reusing or regenerating products and resources throughout the lifecycle of the products to reduce waste and the need for first-use materials. While there was wide agreement that a circular economy rather than a linear one is good for business and the environment, participants also agreed it will be extremely complicated to shift the current global economy away from consumption-based growth. Cultural shifts away from convenience (e.g., single-use plastics, fast fashion, planned obsolescence in tech), and fundamental economic changes in consumer behavior, corporate models, and value chains will be required.

“Perspectives you’ll hear today from academics and industry leaders will illuminate the status quo, as well as the areas where innovation is already helping bring circularity to life, despite the very real challenges,” said Iain McCulloch, director of the Andlinger Center and the Gerhard R. Andlinger ’52 Professor in Energy and the Environment, in his welcoming remarks. “It’s our hope that by bringing talented people together, we can spur knowledge transfer and collaboration that continues pushing in the direction of a circular economy.”

The conference’s keynote speakers used examples like plastic recycling to illuminate the systemic challenges to a circular economy, and ways these can be overcome in the U.S. and other countries. Panel discussions around innovation, scaling, and execution on the ground brought many examples of circularity to life.

Systemic challenges to recycling and circularity

In the first keynote of the day, speaker Andre Argenton, chief sustainability officer and vice president of environment, health and safety at Dow, shared the important role plastics play in various applications in modern life. As a type-1 diabetic who wears an insulin pump daily, he shared his personal experience on the role of plastics as “life-changing enablers in modern life,” Argenton said. He noted that while reducing GHG emissions and circularity for plastics is complex, Dow is determined to reduce emissions from operations and accelerate circular and low carbon solutions.

“I have no doubt we will eventually become much more circular in terms of limiting waste and reusing materials,” he said. “The question is about the pace of that transformation.” He discussed the opportunities for companies like Dow to incorporate more recycled content in products they sell. The fractured recycling system in the U.S. makes it difficult to find enough recyclable plastic to create a reliable feedstock for recycled plastics. Less than 9% of plastic waste is recycled in the United States compared to more than 40% in Europe. With a steady stream of recyclables, companies could produce new materials from recycled materials, but they will only do so if it is profitable.

“The biggest challenge is a clear, consistent demand for recycled plastics,” agreed Adam Gross, senior decarbonization specialist at the Andlinger Center. “It’s very hard to compete with newly extracted materials.” Gross explained that mechanical recycling of plastics, in which plastic is melted, extruded, and reformed without the plastic molecules changing, relies on a supply of clean, homogonous plastic recyclables and is only effective for certain types of plastic goods. Chemical recycling, on the other hand, can process even contaminated and commingled plastics since it breaks plastics down at a molecular level but uses much more energy. Governments can play an important role in bringing down the cost of using recycled material by adopting more stringent recycling requirements and mandating the use of recycled materials.

Innovation and commercialization

Beyond plastics, a circular economy also includes ways to extract and reuse carbon, metals, and minerals, shared Michele Sarazen, assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at Princeton and co-organizer of the conference. Sarazen moderated a panel on innovative approaches in energy efficient and sustainable processes that emphasize closed loops.

For example, “carbon can be removed from urban waste, such as food waste and garbage, and converted to jet fuels, polymers and other products,” said Z. Jason Ren, professor of civil and environmental engineering and the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment. Other chemicals can also be removed from wastewater to both clean the water and recover valuable substances. A founder of Princeton Critical Minerals, Ren and his students have developed a product called “Lilypad” that can extract lithium from brine such as seawater, saltwater lakes, groundwater or industrial wastewater. Lithium is a critical mineral in increasingly high demand that is crucial for the transition to a clean energy economy, vital for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles and renewable energy storage.

Zara Summers, chief strategy officer at LanzaTech, described the company’s novel chemical recycling technology, which uses microbes to convert gases like carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and hydrogen into sustainable aviation and marine fuel and materials for shirts, shoes, and other durable goods. Despite LanzaTech’s innovative technologies, however, as a small company it still faced many pitfalls as it made the transition from the initial idea to a profitable company.

“There are so many great ideas out there, but scaling of technology doesn’t happen in isolation,” said Jennifer Woolfsmith, vice president of sustainability at the petrochemical company NOVA Chemicals. “And circularity doesn’t happen in isolation. It requires deliberate effort to de-risk investments and build systems that work.”

Circularity challenges and solutions on the ground

Challenges associated with the implementation of growing circular processes vary geographically, depending on the national and local infrastructure, laws, and culture, explained plenary speaker Shannon Bouton, the president and founding chief executive officer of Delterra. For developing countries without reliable waste collection and recycling, creating a circular economy is an urgent and often difficult task. In areas where garbage is simply piled up into dumps, communities face an increase in diseases such as malaria and Dengue Fever. Unmanaged waste can also become a global problem causing air and ocean pollution.

Delterra works with cities to build waste management and recycling systems that maximize the quality and quantity of waste recovered. They also work with companies to build markets, demand, and capacity to make these systems more productive and transparent. The organization tailors its approach and its message to each community; for example, in an informal settlement in Buenos Aires, “the motivating factor for them was cleaning up their local environment for their children,” Bouton said.

Delterra works with local government officials in developing countries to set up and enforce recycling programs. The organization achieved a 60% compliance rate and has collected 25,000 tons of recyclables and organics globally. Developed countries can also help by taking responsibility for the waste generated within their borders, and avoiding shipping their waste to countries with infrastructure least able to address it. Extended producer responsibility is one approach being advocated for by nonprofits and adopted by some companies, states, and countries to close this loop by making producers responsible for disposal at the end of their product’s useful life, for example by funding a recycling program.

Circularity at Princeton University

Closer to home, Princeton University, which is in many ways like a municipality, is in the process of revising its own sustainability plan to include a focus on circularity. At the conference, Sarah Boll, executive director of Princeton’s Office of Sustainability, described Princeton’s goal to “strive for zero waste by helping students, faculty, and staff make the connection between consumerism and waste.” The University is first focusing on food waste reduction and has seen early success composting food waste from the dining halls and operating a small-scale aerobic digester through the “S.C.R.A.P. (Sustainable Composting Research at Princeton) Lab.” Students are also contributing to waste reduction through programs like a campus-wide clothing swap and “Mend,” in which they learn to mend clothes rather than discarding them.

Both Boll and Bouton agreed that it is important to understand the communities with which they are working and be flexible when trying to find ways to create a circular economy. “Love your problem, not your solution,” Bouton said. “It’s really important to experiment, collect data, and be ready to say, “This didn’t work,” and move on and try the next thing. Make sure you partner first. There are always organizations on the ground who have tried lots of things and who are very good in that space and will help you build trust.”

“Each of the day’s speakers revealed the difficulties in creating a circular system,” said John Pickering, a behavioral scientist at Evidn and the moderator for the final panel. “The circular economy sounds simple when you frame it as reduce, reuse, recycle,” he said. “But in fact, these systems are extraordinarily complex.”

“We heard from scientists and innovators spending millions to prove small-scale demonstrations, and from others putting hundreds of millions at risk to deploy early-mover industrial-scale demonstrations,” said Chris Greig, co-chair of the annual meeting and associate director of external partnerships and the Theodora D. ’78 and William H. Walton III ’74 Senior Research Scientist at the Andlinger Center, in closing remarks. “They bring extraordinary passion to the problems they are trying to solve, capital and innovation to overcome inevitable challenges, and a determination to help achieve one of the world’s most important sustainability goals.”

Related articles on ‘Circularity’: