Morgan Kelly, High Meadows Environmental Institute

The heavy snowfalls and frigid days of this past winter in New Jersey let Princeton sophomore Grace Liu finally experience the Northeastern winter she’d only imagined growing up in her Florida hometown of palm trees and sandy beaches. She was one of the many Princeton students who returned to campus in January in time for traditions of building snowmen across campus and scaling mounds of plowed snow as tumbling flakes stuck to their knit hats and coats.

One tradition stuck in Liu’s mind for its absence, however. For the sixth year in a row, winter has passed without Princeton’s Lake Carnegie being opened for ice skating, despite how low temperatures fell. According to an ongoing project Liu began last summer as an environmental intern in Princeton’s High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI), next year may be the same.

A computer science major, Liu is working with her advisers Gabriel Vecchi, professor of geosciences and the High Meadows Environmental Institute and associated faculty of the Andlinger Center, Nadir Jeevanjee, a research physical scientist at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, and Sirisha Kalidindi, a postdoctoral research associate in Vecchi’s research group, to determine if the lake not being suitable for ice skating since the winter of 2014-2015 is part of a larger trend linked to climate change.

For the initial phase of the project, Liu spent last summer determining the years since the lake’s construction in 1906 when the lake froze enough for skating. Because there’s no official record of when the lake has been open for skating, Liu developed a unique method of combining past media accounts and her own interviews with people at the University and in the community to create a timeline of the years when skating was allowed.

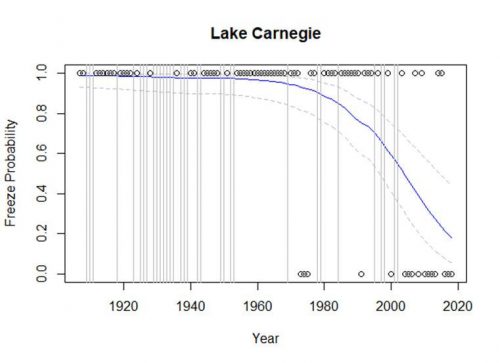

With the resulting dataset, Liu and her advisers found that the chances of ice on Lake Carnegie being thick enough to skate on has plummeted since 1950 and by more than half since 2000. “The freeze proportion has decreased pretty alarmingly in the past several years,” Liu said. “Within a matter of decades, the probability of safe ice skating on Lake Carnegie has dropped from 1 to 0.2.”

In other words, recent winters have seen only a 20% chance the lake would freeze, down from nearly 100% as recently as the late 1960s. “We now have whole class years that didn’t get to go out skating on the lake once during their time at Princeton,” Vecchi said. “We may be entering a time when, if you come to Princeton, there’s a decent chance you won’t get to skate on the lake.”

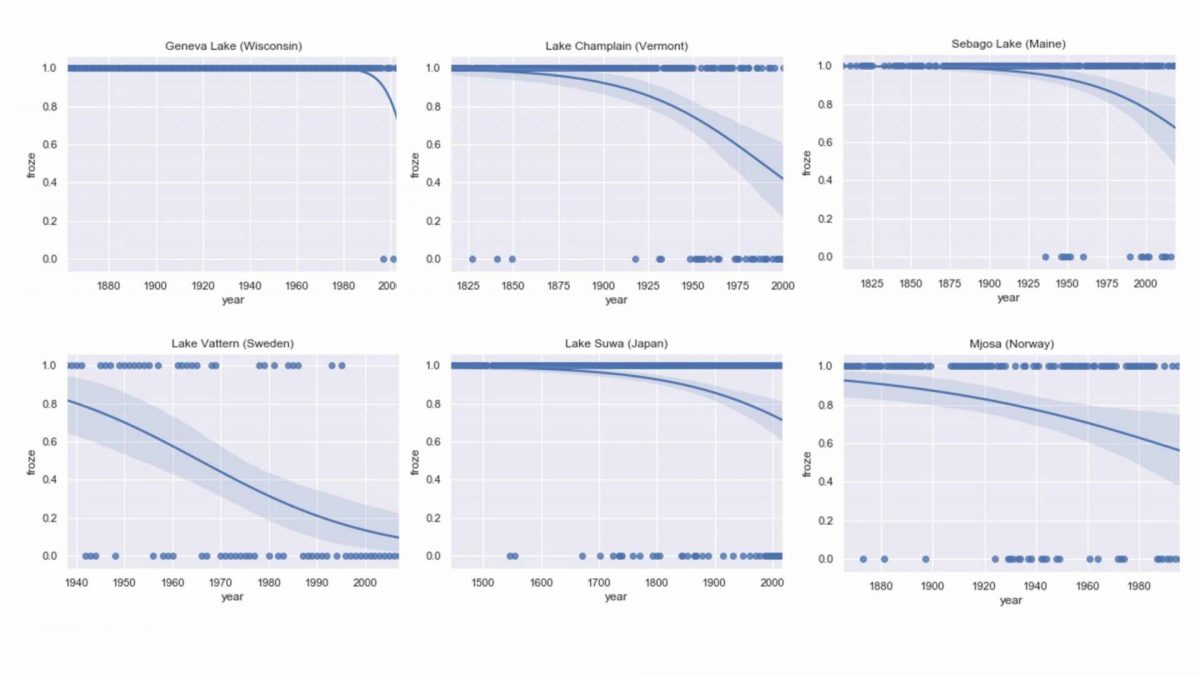

But this work goes beyond predicting when Princetonians can strap on their skates. Liu compared their findings to 19 intermittently frozen lakes — meaning they freeze in some years but not others — around the world. Using the National Snow and Ice Data Center’s Global Lake and River Ice Phenology Database, she found that Lake Carnegie’s increasingly infrequent freezes match what has been observed globally.

“Some lakes have frozen every year up until recently, while others had a clearer intermittent pattern,” Liu said. “But when we look at the aggregate freeze proportion for these lakes, we notice it is decreasing overall. In the past five, 10 or 15 years, the amplification of climate change has definitely been consistent with what we saw.”

Bringing climate change home

“Climate change can feel abstract to many people, especially if their lives are not impacted by sea-level rise or extremes such as hurricanes and wildfires,” said Jeevanjee, who, as a Hess Fellow postdoctoral researcher in Princeton geosciences, developed the project with Vecchi. “I thought this project would bring climate change home in a way that weather statistics do not.”

The project is a good opportunity to study local effects of climate change, which are usually overshadowed by research on global-scale changes, Vecchi said. “Adaptation to climate change will require some very local decisions,” he said. “To make them wisely, we will need to have a basis to understand the very local impacts of climate whenever possible. There are likely implications to the ecosystems in and around Lake Carnegie that would be worth thinking about.”

In Florida, Liu said, people relate to sea-level rise not through climate-model projections, but by experiencing flooding, extremely high tides and loss of property: “I was interested in how other people may experience climate change.”

“Recreation isn’t something that we talk a lot about when we talk about climate change,” Liu said, “but something like ice skating is something that people notice — the lake freezes or it doesn’t. When people see how climate change affects their activities and what they like to do for fun, it can send the message that it actually affects us personally.”

Vecchi himself was motivated by the fun of skating on the lake with his family in early 2015 — only to learn that the experience used to be more commonplace. “Talking with friends who’ve lived in the area for a while, they told me that skating on the lake wasn’t always the rare event it is now,” he said. “So it seemed like an interesting question to ask — had the lake actually been freezing less?”

Liu first pored over the archives of local newspapers such as The Daily Princetonian and Town Topics, which reported on when skating took place or when it didn’t. Daily Prince articles from 1914 and 1922 even specified the ice’s thickness.

In some articles, the ice was more tangential, but its presence was noted. A Daily Prince article from March 1941, for example, mentioned how “the thawing waters of Lake Carnegie” had finally revealed the body of German chemist Erhard Fernholz, who had accidentally drowned in December 1940, his disappearance at one point prompting the FBI to investigate it as a possible Nazi-involved assassination.

One of the interviews Liu conducted to supplement her media data was with Princeton native John Cook, a graduate of Princeton’s Class of 1963 and record-holding Princeton men’s hockey player who has lived a half-mile from the lake for 70 years.

He recalls from his first memories in 1945 through the 1960s that the lake would be thronged every winter with people skating, playing hockey and even ice sailing. By the 1970s, much of that activity had vanished. While regulations for using the lake tightened during that time, the days of available ice have certainly diminished, Cook said.

“The available science on climate change hasn’t really shaped my view of the change in winter conditions,” Cook said. “On the other hand, I have noticed a gradual change in winter temperatures over the past 75 years that has reduced the number of days in which we can skate. It is pretty obvious that the climate has changed and my reduced time on the outdoor ice over my life supports that.”

Liu’s work uncovered a surprising social response to climate change — as the lake froze over less often, the lack of skating became normalized. “By looking at the historical record, we saw this shift in how people perceive ice skating as something that’s expected to something that is a rare treat,” Liu said.

A Town Topics story from 1960 reported that that year “will go into history as the first winter in 14 years that failed to produce outdoor skating at any time.” On the other hand, in 2007, the Daily Prince celebrated the lake “freezing over for the first time in several years.”

“This is revealing evidence that as climate changes, one of the ways we adapt to it is by changing what we expect,” Vecchi said.

What a tiny lake says about a changing world

Any climate scientist will caution against conflating weather with climate. But the freezing of a lake — even a small one — might include enough longer-term factors to provide a snapshot of larger phenomena, Jeevanjee said.

“Part of why this worked is because ice integrates weather over several days and weeks — solid freeze-over and melting cannot occur overnight,” he said. “The freeze record of Lake Carnegie should be a better indicator of climate than more transient weather events such as extreme snowfall.”

Because of that, when people notice patterns such as a lake freezing less often, it may be more indicative of climate change than personal accounts typically are, Jeevanjee said.

“The anecdotal accounts from this project seem to be supported by both the newspaper data we collected as well as the usual global temperature datasets,” he said. “Thus, our modeling results have a direct correlation with people’s expectations. This adds a human element to our analysis, and also puts people’s intuitive expectations on a rigorous footing.”

People have used written records and personal accounts from, for example, the Caribbean or China to build estimates of past changes in typhoon or hurricane activity going back a few hundred years, Vecchi said. “One must do careful work like Grace has been doing to tease out the extent to which climate is reflected in individual experiences,” he said.

“Grace presents clear evidence of the utility of newspaper accounts in recording relevant climate information,” Vecchi said. “I think that there is potential to use this type of method for other climate change effects, though it will depend on the phenomenon, the quality of the records, and how strong a climate connection one may expect.”

Liu is continuing the project outside of her coursework by refining the data she’s already produced and building machine learning tools to interpret and project lake-ice changes. She’s also starting to examine the factors that influence ice formation, such as the number of days below zero, cloud coverage, and fall and winter temperatures — and how they might be changing as the planet warms.

“We know that lake freezing is decreasing over time, but we also want to know what variables are causing that in terms of temperature and climate,” Liu said.

“Our hope,” Vecchi said, “is that by connecting the freeze of Lake Carnegie and other lakes to larger-scale environmental conditions, we can build some sort of capability to predict the likelihood that a lake will freeze in a given year, or how these odds are changing.”

This story originally appeared on the High Meadows Environmental Institute’s website.