By Molly A. Seltzer

Capturing carbon at the smokestack is a promising way to combat climate change, but the majority of Americans are unfamiliar with the technology, according to a new study from Princeton University.

“It’s a signal that more communication is necessary to the general public,” said Elke Weber, the senior author of the study, who is the Gerhard R. Andlinger Professor in Energy and the Environment and a professor of psychology and the School of Public and International Affairs.

“Right now, the technology has entered the policy space, but it has not trickled down to gain the level of recognition that wind and solar enjoy among the American public,” said Weber.

Carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) has surfaced as a tool for stymieing climate change that is gaining traction among politicians and industrialists alike. The CCS process involves capturing carbon dioxide gas from facilities — such as fossil fuel power plants, factories and refineries — before it enters the atmosphere and then piping it underground for permanent storage. CCS promises to reduce emissions from industrial processes like steel and cement production that are difficult to decarbonize. But critics cite concerns with the technology’s high cost and challenges in identifying viable storage sites. They also say it’s a way to extend the life of fossil fuel plants and pay a windfall to their owners.

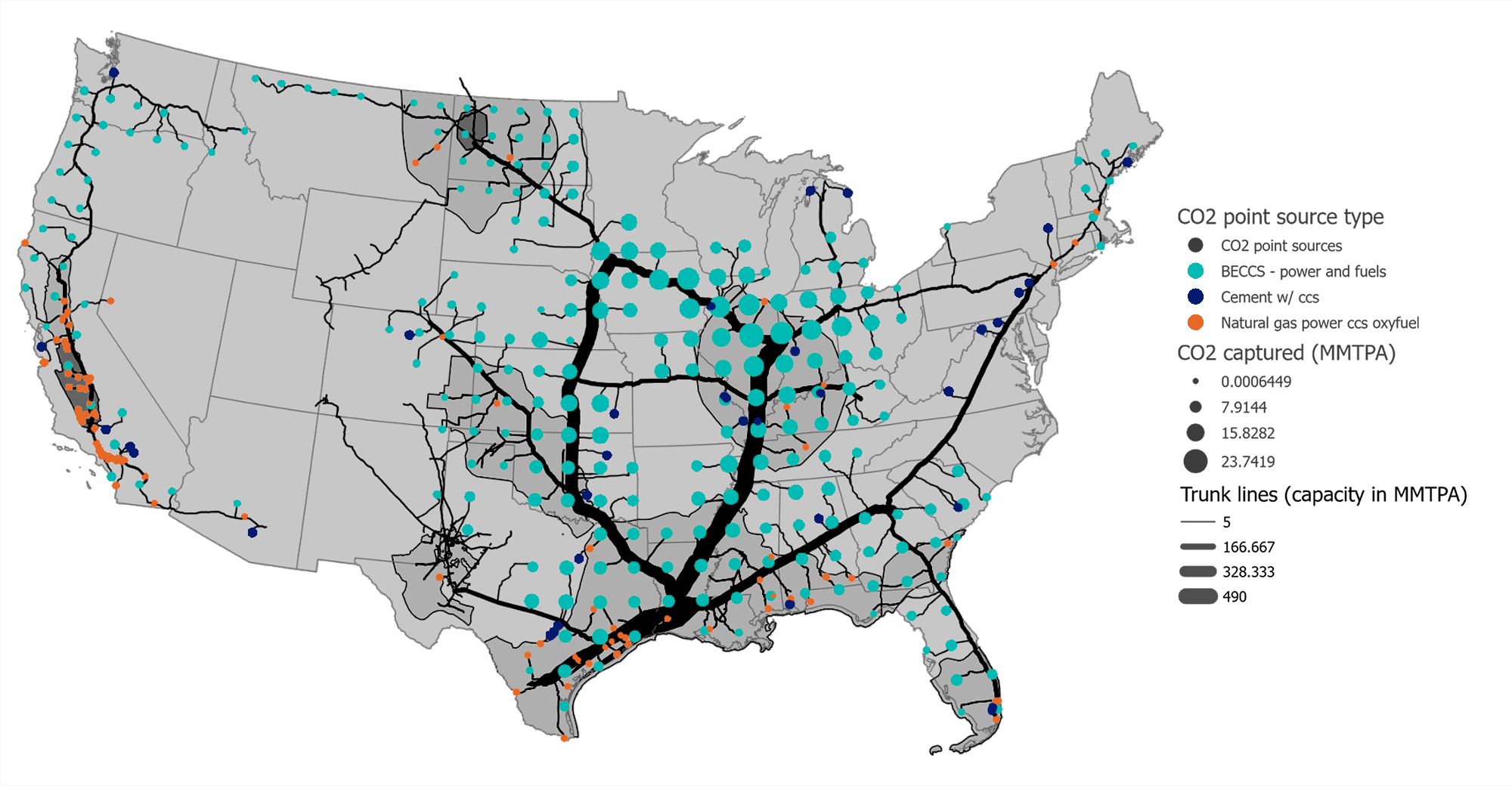

Despite the criticism that the technology benefits the oil and gas sector, many see it as a crucial technology for preventing further buildup of atmospheric carbon dioxide and further planetary warming. Princeton’s Net-Zero America (NZA) study, released in December, mapped out five technological pathways through which the United States could achieve net-zero emissions. (The goal of “net-zero emissions” means adding to the atmosphere no more carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases than are permanently removed from it.) Carbon capture is a key technology in all of the NZA scenarios; in one of the five, the carbon is used instead of sequestered underground, a concept known as carbon utilization.

Click to enlarge (Source: Net-Zero America report: https://netzeroamerica.princeton.edu/)

According to Weber’s research, published in the journal Energy Policy, over 80% of Americans either do not know of the technology or could not definitively say that they recognize it, which points to a gap in communication.

Weber said part of the reason Americans may not know about CCS is because they generally don’t see it. While CCS can theoretically work any place there is a smoke stack and a concentrated, steady waste gas stream, there are only 21 commercial, large-scale plants globally where CCS is currently being used, most of them in the United States and Canada. The waste carbon from the 21 plants is generally used for enhanced oil recovery, a process that pumps the recovered carbon dioxide into oil wells to get more oil from them and then stores the carbon dioxide permanently in the well, though there are other potential uses for the captured material like making chemicals and plastics or turning it into liquid fuels.

Weber said it’s important to educate the public more fully about the merits, risks, and need for the technology before carbon capture plants are proposed in more areas and communities.

“If researchers are more proactive in how the technology is being introduced and communicated to the public, the scientific community can have more of an influence on how it’s perceived by the public, rather than allowing divergent and ill-informed narratives to propagate. I see the fact that there is little public information on the topic and technology as an opportunity for storytelling and education campaigns,” said Weber.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), there are 12 carbon capture, utilization and storage “hubs” — industrial centers that utilize shared carbon transport and storage infrastructure — in development around the world. Carbon capture has been used at fertilizer, chemical, natural gas and power plants. At these facilities, carbon dioxide can be captured at a relatively low cost. But the IEA report noted that in other areas, including cement and steel, deployment has a long way to go. And according to the NZA study, the technology would need to scale up significantly in order to be effective at mitigating climate change. NZA estimates show that in order for the United States to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, the country may need to transport more than double the amount of oil that is being moved through pipelines today in carbon dioxide by equivalent volume.

The researchers of the public perceptions study found that Americans who know about carbon capture generally perceive the technology to have net positive benefits because of the opportunity to mitigate climate change. The researchers said they did not delve into why those who recognized it saw it as a force for good, but hypothesized it could be because information about carbon capture is often disseminated by companies and organizations in favor of the technology.

While less than 20% of those polled had heard of CCS, once it was introduced to participants, it became clear that support for the technology varies depending on the policy tool used to implement it. When the researchers tested various policy instruments, they found that state-level bans on the construction of new fossil fuel power plants without CCS enjoyed high support, compared to state-level subsidies on CCS or taxes on unabated fossil fuel power generation. This means that Americans would rather states ban new coal or natural gas plants that do not capture carbon at the smokestack than subsidize the CCS technology or penalize polluters.

“Public support crucially depends on specific policy design features,” said Silvia Pianta, lead author on the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the European Institute on Economics and the Environment.

“Once in the policy design phase, it’s really important to take into account all of these different features; it’s not just a general question of whether or not to promote the scale up of CCS, but also of how the public could perceive different policies to promote CCS,” said Pianta, who is also a Ph.D. Fellow at Bocconi University in Milan.

Respondents who perceived climate change as a more imminent threat or risk to themselves also demonstrated more positive views of CCS. The research also found that having a higher income was linked to more positive perceptions of carbon capture, and so was residing in urban areas. Age and education were not significant indicators. The authors also learned that CCS infrastructure will have higher chances of political survival in less densely populated areas where new infrastructure installed at industrial plants is relatively far away from residential areas.

When it came to political ideology, the research demonstrates that carbon capture is subject to the same entrenched political beliefs that have affected climate perspectives and action in the United States for years. Democrats generally registered more positive perceptions of the technology, presented as a climate solution, compared to Republicans.

“The ideological polarization around climate change needs to be taken into due account when proposing, communicating and implementing policies to scale up CCS in the United States,” said Weber.

The researchers suggested more work needs to be done to understand the potential impact of communicating the job creation benefits or other positive economic implications, and if those efforts would increase support among independents and conservatives. The authors pose another option, too, which is to frame the technology in terms of energy security benefits.

The researchers said they focused on the United States for the study, in part, because it is a leader in the development of carbon capture technologies so far, and because they anticipated that it would be an insightful case study, given the stark divides between the two political parties.

“There has been a surge in research on the technical challenges associated with CCS technologies, but we still know very little about the socio-political challenges,” said Adrian Rinscheid, a co-author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland.

They also cited several operational CCS plants in the United States and a strong oil and gas industry that has experience with massive infrastructure for piping gas across the country and underground as reasons for studying the U.S. populace. Pianta said that the U.S. government is investing more in CCS than other governments have and it has created a relatively supportive policy environment for CCS with the passage of the 45Q legislation in March 2018. This legislation broadened eligibility for a tax credit to entities that capture and store carbon dioxide, and there are additional proposals for new large-scale, private-public projects and to expand 45Q.

But there is still more engagement to be done with the American populace on this topic.

“I don’t think it’s a simple story of ‘The more, better information about the risks and benefits of the technology that is available, the more public acceptance there will be.’ It could go in a different direction. The study does suggest that the American public doesn’t know much about the technology, and so there is an opportunity to create narratives that inform on the topic, and to create targeted messaging for each segment of the population,” said Weber.

Related articles:

- KAIST and the Andlinger Center at Princeton University Announce Net-Zero Korea Study to Accelerate Korea’s Energy Transition

- Research incorporating risk into energy system modeling funded by Andlinger Center innovation grant

- Net-Zero America: How state policymakers can use data from Princeton’s pioneering study to meet climate goals