Young leaders from around the world played a game that demanded they solve climate change. Balance proved best.

By Aaron Nathans, Office of Engineering Communications

It was just a game, sort of, but a daunting challenge nevertheless: Find a way to ramp up energy production to serve a growing population, without increasing net carbon emissions, by 2050.

Jesse Jenkins, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment, tasked eight small teams of young professionals from around the world with figuring out an energy mix to balance national and world clean energy goals with power reliability and affordability.

For many participants, this game was harder than it first appeared – especially with the potential for natural disasters and not-in-my-backyard pushback against renewable energy construction projects like wind.

“This is seriously causing some stress here,” Dorjee Sun said, staring at the game board and balancing his faith in environmentally friendly energy against some of the mitigating factors the game forced his team to contemplate.

The game was the centerpiece of “Advancing the Global Energy Transition,” an executive education program at Princeton University June 26 to 29. The program was hosted by the World Economic Forum and its Young Global Leaders program, as well as the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment and Princeton University. It was made possible by the generous gift of Howard Cox, special limited partner of Greylock Partners.

The 38 participants from the global leaders program were executives, entrepreneurs, government officials, academics and writers from 20 countries. This was the second such executive education event held at Princeton; the last was in 2018. In addition to the role-playing game, the four-day course included panel discussions and keynote talks by experts in academia, industry, non-profits, and government.

Claire Gmachl, interim director of the Andlinger Center and the Eugene Higgins Professor in Electrical and Computer Engineering, said the event showed the importance of building coalitions to secure the world’s energy future. “We endeavor to educate decision-makers and stimulate ideas through diverse groups that will ultimately help secure the global energy and environmental future.”

The game was hypothetical, but its problems and supporting data were real. The game used as its reference point the Net-Zero America study co-authored by Jenkins. The report, released to much news coverage in December 2020, envisioned what it would take for the U.S. to achieve an economy-wide target of net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050.

At the event, Jenkins described “net zero” as, “the point when we stop digging a deeper hole” – limiting additional future damage to the environment as opposed to stopping the harm already done.

“People don’t remember if you lost the game; people remember if you destroyed the planet,” said Amit Mehra, a member of the winning team who works as a sustainability executive at the global technology firm, Accenture.

Participants were able to pull levers within four areas: clean electricity (like wind and solar); energy efficiency; net-zero fuels (like nuclear, hydrogen, and fusion); and carbon capture and sequestration.

Although clean electricity was “the linchpin” for a net-zero economy, Jenkins said the job ahead requires much broader thinking. Meeting climate goals would require enough new clean electricity generation to satisfy a 115-170 percent projected growth in future demand, he said. “This is a staggering amount of infrastructure to build.”

He noted costs of wind, solar and battery storage have dramatically declined over the last decade. Nevertheless, in order to reach net zero carbon emissions, many different forms of energy are needed, he said. The sun isn’t always shining, and the wind isn’t always blowing, he said.

“You can’t ignore any of them and still get the job done. You want a balanced diet.” Jenkins instructed the group. “I hope you figure it out,” Jenkins said, to nervous laughter from the assembled participants, as he sent the teams into breakout rooms to save the planet.

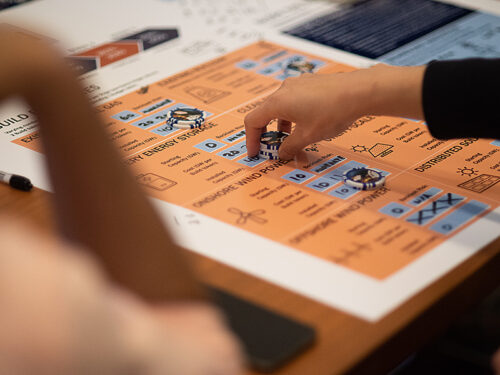

In the breakout rooms, participants held poker chips, talking amongst themselves about which fuels to place their bets on. Should they stay away from renewable fuels with potential backlash? Should they ignore the rules of the game and try and go all-in on utility-scale renewables? They moved their chips around on the game board, trying to balance clean energy with reliability and affordability.

Some participants, especially those who came in ready to go all-in on renewable power, discovered as they fed their plans into the game’s computer program that they needed more traditional forms of energy like natural gas to tide them over as more innovative forms of energy were developed, became more cost-effective, and gained social acceptance.

“We learned that in the real world, the challenges are bigger than we could have thought,” said Lin Yang, whose digital media company showcases work by entrepreneurs in areas that will soon include energy and sustainability. She said the program helped her learn the vast scope of the technical and international political barriers to a sustainable future.

“This was a reality check,” said Sun, who noted he came in excited to ramp up renewables fast, but whose team in the end settled on a more balanced approach. Sun founded Bioeconomy, which works to conserve and restore natural habitats across the world. He’s been named a “hero of the environment” by Time magazine. “We were trying to create a utopia. But we were forced into a reality.”

Even as they wrestled with these decisions, the participants heard from range of experts from academia and industry providing more context, and reminding them that every choice in their “game” represents much work to build coalitions and partnerships across diverse sectors and communities.

“We are going to have to cooperate and undertake partnerships in ways not seen before,” said Martin Parkinson, chancellor of Macquarie University in Australia. “It will require us to think about how we operate up and down the supply chains, and it’s going to require regulators to remove restraints, allowing firms to work more closely together.”

Wind energy was an example of a new technology needing a lot of coordination.

“This is a massive public works project at its heart,” said Abe Silverman, chief counsel to the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities, referring to offshore wind. It isn’t just building and erecting the turbines, he said. There’s also feeding the power into the grid, and then transmitting it around the region.

Madeline Urbish, head of government affairs and market strategy in New Jersey for Ørsted, the U.S. leader in offshore wind, said public policy plays a vital role in moving new electricity sources forward. “Policymakers and industry must work together to meet the needs of the state.” Urbish said. “Clean energy development presents an enormous opportunity for communities across the country.”

Elke Weber, the chair of the Young Global Leaders education program and associate director of education at the Andlinger Center, said that in observing the 38 leaders at work she was encouraged to see that “the urgency and unprecedented scale and speed of necessary technological, political, economic, and social change” has galvanized them to take on the challenges in all their complexity. Participants, she said, seemed equally eager to pursue climate mitigation and adaptation, equity and justice, and good-but-not perfect solutions needed to make practical progress.

On the last day, the teams returned to Maeder Hall to explain how they would strike a balance of fuels going forward to 2050. Some teams went in big on fusion; others kept natural gas and nuclear fission as a baseload power and ramped up on and offshore wind and solar in a big way.

The participants’ engagement was heartening, said Chris Greig, acting associate director for external partnerships at the Andlinger Center. They embraced the massive challenge of the energy transition, including the scale and speed of new infrastructure investments, the need for public buy-in, and the importance of partnerships across borders, Greig said. “We don’t get a second chance at the transition.”

In his address to the participants at the event’s farewell lunch, University President Christopher L. Eisgruber emphasized that this is a critical time for the planet, and the job ahead is anything but hypothetical. “The future of the world depends on you making progress.” he said.